The Hard Way of Emulating Firmware Part 1

It is not your fault when it’s not working.

André Eichhofer

Happy day,

Today I want to focus on the emulation of firmware. This is not an easy task and will cost a lot of nerves while the success is not guarenteed. Emulation means to execute something in a special, containerized environment that is originally designed for a different system. With regards to firmware you can take for example a router. Its firmware is normally stored on a microcontroller within the device. You switch on the router and be able to access a web interface. However, you could also try to obtain the “operating system”, the firmware, from somewhere else and run it in your own environment. You could do that, for example, to analyze the behaviour of the software, to find vulnerabilities or to test exploits whithout having the physical device at hand. However, in most cases the router firmware would demand a different operating platform. Nevertheless, you can emulate the firmware if you create the proper environment on your machine.

So, the first question you may ask is where to get the firmware? Well, a lot of vendors have firmwares on their websites. I will later in part 2 present a tiny little script that scrapes firmware from different vendors.

When we emulate processes we can differentiate between two kinds of emulation: We can emulate only a single executable without regards to other dependencies. This is called static or user mode emulation. Or we can try to emulate a whole system or firmware. This is called dynamic or system mode emulation.

User mode emulation

Let’s start with user mode emulation, because this should belong anyway to the first steps when testing firmware. From our firmware system we will pick up a single binary and try to run it. Be aware that with static emulation you can most probably not analyze the system completely.

Before we start we need to prepare our firmware. As an example I take the Totolink EX200 firmware V5.2.3c.

After you’ve downloaded the firmware, extract the file system with a tool of your choice, here I use Binwalk.

binwalk --run-as=root -eM totolink-x200.web

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

174104 0x2A818 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 8388608 bytes, uncompressed size: 3575780 bytes

1178682 0x11FC3A Squashfs filesystem, little endian, version 4.0, compression:lzma, size: 1569573 bytes, 686 inodes, blocksize: 131072 bytes, created: 2038-07-30 02:35:44

...

...

...We’re interested in the squash-fs filesystem, so we navigate into the extracted directory:

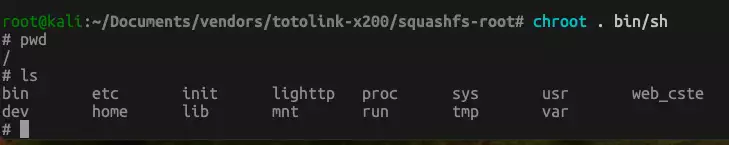

root@kali:/Documents/vendors/totolink-x200/squashfs-root# ls

bin dev etc home init lib lighttp mnt proc run sys tmp usr var web_csteLet’s do some tests and determine what architecture the firmware requires. Pick-up a random executable from the firmware and examine it with the file command:

# file /bin/busybox

busybox: ELF 32-bit MSB executable, MIPS, MIPS-I version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-uClibc.so.0, no section headerWe see the architecture that the binary requires is 32-bit, msb (big endian) and a MIPS processor. In addition we see that the file is dynamically linked, thus it requires an external library.

In comparision, we can check the architecture of our own machine when we examine a random binary from our file system:

file /usr/bin/ls

/usr/bin/ls: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, ARM aarch64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-linux-aarch64.so.1, BuildID[sha1]=87a7eadc711cd002f7b00ba923179e5713498159, for GNU/Linux 3.7.0, strippedWe see that the architecture that our host system binary demands is 64-bit, lsb (little endian) and an ARM processor. That means, the binary located in the firmware will not run on our system, as we can see:

root@kali:/Documents/vendors/totolink-x200/squashfs-root# chroot . busybox

chroot: failed to run command ‘busybox’: Exec format errorEmulate it with Qemu

Here, Qemu comes into play. Qemu is a software that allows you to run executables that are compiled for one CPU on another CPU. Learn more about Qemu, here.

To statically emulate a process on your machine, you first need to identify the proper Qemu binary. In our example, we deal with MIPS 32-bit architecture, big endian. For that architecture we use qemu-mips-static.

Navigate to your firmware root folder and copy the Qemu emulator there (cp $(which qemu-mips-static) .). Then execute Qemu with the desired binary: chroot ./qemu-mips-static bin/busybox

BusyBox v1.13.4 (2020-12-11 09:52:38 CST) multi-call binary

Licensed under GPLv2.

See source distribution for full notice.

Usage: busybox [function] [arguments]...

or: function [arguments]...We have successfully executed Busybox from the firmware on our system.

We can even start the firmware shell using: chroot ./qemu-mips-static bin/sh

Now, we try to run the web server of the embedded device.

Totolink EX-200 uses a Lighttpd web server that is located under bin/lighttpd and uses a config file under lighttpd/lighttpd.conf

To start the web server we run chroot ./qemu-mips-static bin/lighttpd -f lighttp/lighttpd.conf -m lighttp/lib/

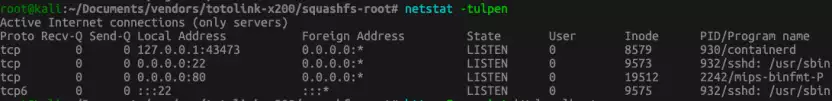

Using netstat -tulpen we see that the web server really started on localhost at port 80.

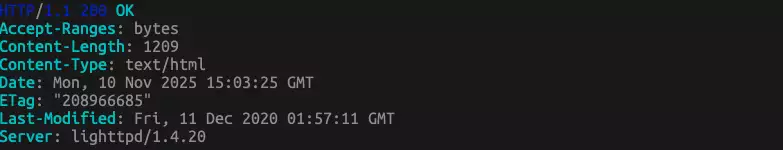

Let’s make a command line request to the web server, http -F --print hH localhost

We can even open a browser at localhost.

However, except of a favicon we do not see anything. This is, because we only statically emulated the web server, so it didn’t load the resources that are needed for the user interface. To test more functions, we probably need to emulate the firmware dynamically. Check up part 2 of this post.